In contrast with the previous discussion, this section relies less on caseload statistics and more on survey results, legal analysis, and key informant interviews.The case management systems do not generate reports that could be used for determining the procedural causes of delays, or indicators that might be used to track improvements.266 Such capabilities are available but data is not entered. It will be important to remedy this oversight to ensure that procedural efficiency can be monitored and improved through the collection and analysis of data.267

Improved procedural efficiency likely requires a suite of targeted and calibrated reforms, which will need to be effectively monitored.

In contrast with the previous discussion, this section relies less on caseload statistics and more on survey results, legal analysis, and key informant interviews.The case management systems do not generate reports that could be used for determining the procedural causes of delays, or indicators that might be used to track improvements.266 Such capabilities are available but data is not entered. It will be important to remedy this oversight to ensure that procedural efficiency can be monitored and improved through the collection and analysis of data.267

Improved procedural efficiency likely requires a suite of targeted and calibrated reforms, which will need to be effectively monitored.

Box 8: Innovation and Efficiency Stifled in Novi Sad

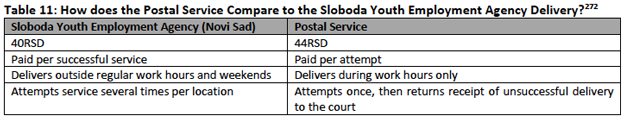

The Misdemeanor Court in Novi Sad used the Sloboda Youth Employment Agency as its internal delivery service in the city of Novi Sad as well as the municipalities in Veternik, Futog and Petrovaradin. Sloboda couriers were paid 40RSD per successful delivery. According to the Misdemeanor Court, success rates ranged from 75-80%, resulting in the delivery of 7,000-10,000 documents per month. Their couriers repeatedly attempted service of process for the same price by going several times in a single day to the address of the party. They also provided the court with observations from the field, which facilitated further procedural steps such as advising if the address was invalid or if the person no longer lived there. Couriers were also willing to work after regular work hours and on weekends, when residents are more likely to be home.

According to the Court President:

‘Sloboda provided an astounding contribution to more efficient operation of the court, in pre-trial process, during court proceedings, and later in the phase of enforcement of court decisions. They also facilitated more effective enforcement of deadlines that are essential in legal proceedings, and therefore helped us reduce the number of cases that collapse by falling under the statute of limitations. Their work significantly improved our fines collection rate and increased inflow of funds to the budget.’

Despite the success, the Misdemeanor Court discontinued its cooperation with Sloboda in 2014. The 2014 budget for the court was only partially approved, and the line item for internal delivery service was cut to one-quarter of the sum. The Misdemeanor Court returned to using the postal service, where it is safer to accumulate arrears, and expenses can be more easily masked within general administration.

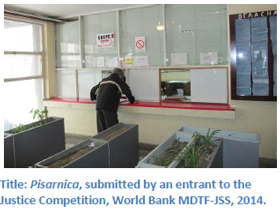

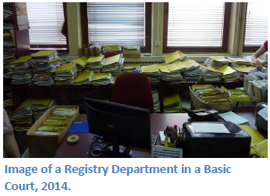

A further frustration is the delay caused by transferring case files. In cases which transfer between

courts, it can take several months for the file to be

transferred from one court to another, even when the two

courts share the same building. This process clearly slows

down the resolution of the dispute and is unsatisfactory from

the perspective of the parties. During the two painful re-

organizations of the court network in 2010 and again in 2014,

there were serious problems in locating and transferring files

between courts and between PPOs. On some occasions, files

have been misplaced or lost altogether. With a disorganized

filing system (as shown in the picture here) there is always room for mistakes and potential abuses. Such dysfunctions can be simply remedied through basic document

management, the use of barcodes and increased use of available scanning technology

A further frustration is the delay caused by transferring case files. In cases which transfer between

courts, it can take several months for the file to be

transferred from one court to another, even when the two

courts share the same building. This process clearly slows

down the resolution of the dispute and is unsatisfactory from

the perspective of the parties. During the two painful re-

organizations of the court network in 2010 and again in 2014,

there were serious problems in locating and transferring files

between courts and between PPOs. On some occasions, files

have been misplaced or lost altogether. With a disorganized

filing system (as shown in the picture here) there is always room for mistakes and potential abuses. Such dysfunctions can be simply remedied through basic document

management, the use of barcodes and increased use of available scanning technology