Box 3: Backlog Reduction in Action: a Story from Vrsac

The Vrsac Basic Court has significantly improved efficiency and reduced its backlog through a series of initiatives. These were led by two successive acting Court Presidents with the support of a core managerial team of skilled court staff, and the advice of the USAID SPP.

The Court Presidents focused on using court statistics to monitor judges on a weekly and monthly basis, comparing the number of resolved cases and the ratio of new and old resolved cases among different judges. Using an ‘I'm watching you’ strategy, each of the Court Presidents encouraged judges to work more efficiently, and not neglect old and difficult cases in favor of new and easy-to-resolve cases.

The Vrsac Basic Court did the same with the routine monitoring of progress in unresolved enforcement cases by court bailiffs. Once bailiffs knew that their work was monitored, the pace of resolution in enforcement cases improved dramatically. Outreach to the public with accompanying incentives also encouraged enforcement defendants to pay out their debts. For further discussion of enforcement, see below.

The Vrsac Basic Court also introduced simple layman’s checklists and forms for parties unfamiliar with court procedures, whether due to education, language, or socio-economic status. One such checklist, on how parties need to fill-in and file documents helped ensure that cases ran more smoothly. That practice became more complete and uniform. As parties became easier for judges to work with, the valuable time of judges could be better spent on judicial work.

The Vrsac Basic Court and Prosecutors Office increased their use of deferred prosecution, thus decreasing the inflow of new minor cases that could be readily dealt with in other ways. This allowed the court to focus on resolving cases. For further discussion of deferred prosecution, see the Quality Chapter.

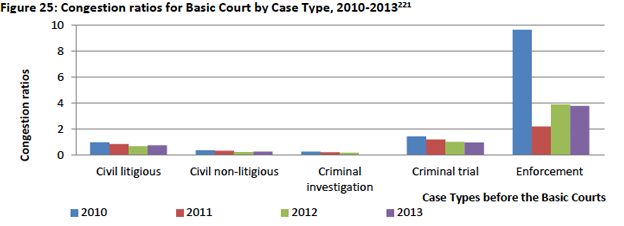

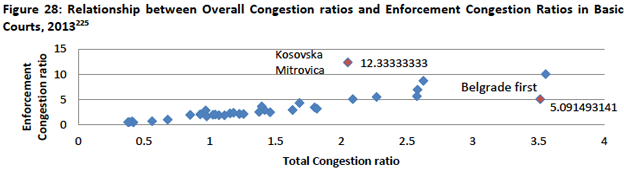

The experience of the Vrsac Basic Court demonstrates a holistic approach to backlog reduction, which was led by two proactive Court Presidents at minimal cost. Congestion ratios dropped from an alarming 9.8 in 2012 to 2.6 in 2013.

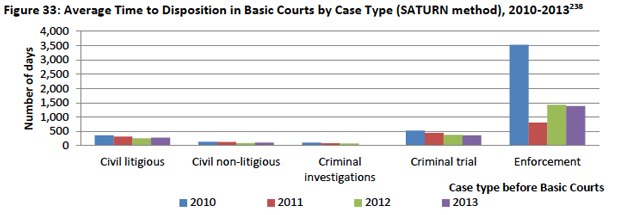

Box 4: What is the SATURN Methodology?

Case turnover ratio: Relationship between the number of resolved cases and the number of unresolved cases at the end of each year.

Case turnover ratio = Number of resolved cases / Number of unresolved cases at the end

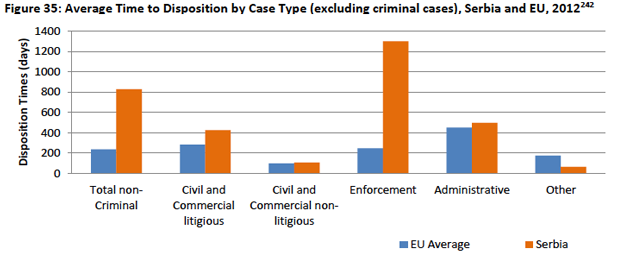

Disposition time: The turnover rate is actually the congestion ratio inverted. Here it is divided (or multiplied) by 365 days to reach an approximate time for case resolution. The ratio measures how quickly the court turns over received cases, or in other words, how long it could be expected to take for a type of case to be resolved.

Disposition time = 365 / case turnover ratio or 365 X congestion ratio

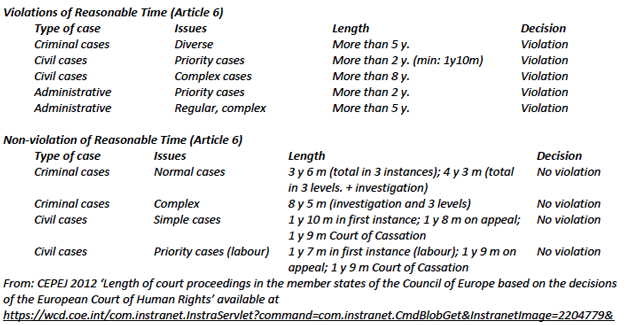

Box 5: How Long is Too Long? ECHR Timeliness Standards

There are no clear-cut rules for what constitutes a ‘reasonable time’, as every case must be considered separately. However, an analysis of a large number of cases before the ECtHR provides a useful indication of the approach taken by the ECtHR in interpreting Article 6 of the ECHR. The following can be established: