As the saying goes, ‘justice delayed is justice denied.’ Yet, across the world, court users complain that the courts take too long. For your regular court user facing endless talk from lawyers, reams of paper, and mounting legal bills, a court case can feel like it goes on…FOR….EV….ER.

As the saying goes, ‘justice delayed is justice denied.’ Yet, across the world, court users complain that the courts take too long. For your regular court user facing endless talk from lawyers, reams of paper, and mounting legal bills, a court case can feel like it goes on…FOR….EV….ER.

But how long is too long? The question has arisen on each of my last four missions in as many months – from Kenya to Croatia to Serbia and back.

And it’s not a rhetorical question. Answers can assist client countries in analyzing their efficiency and devising reforms that improve both timeliness and user satisfaction. It also enables potential court users to better estimate how long it might take to resolve their dispute – allowing them to then adjust their expectations accordingly.

After all, better enabling people and businesses to resolve their disputes contributes to poverty reduction and shared prosperity.

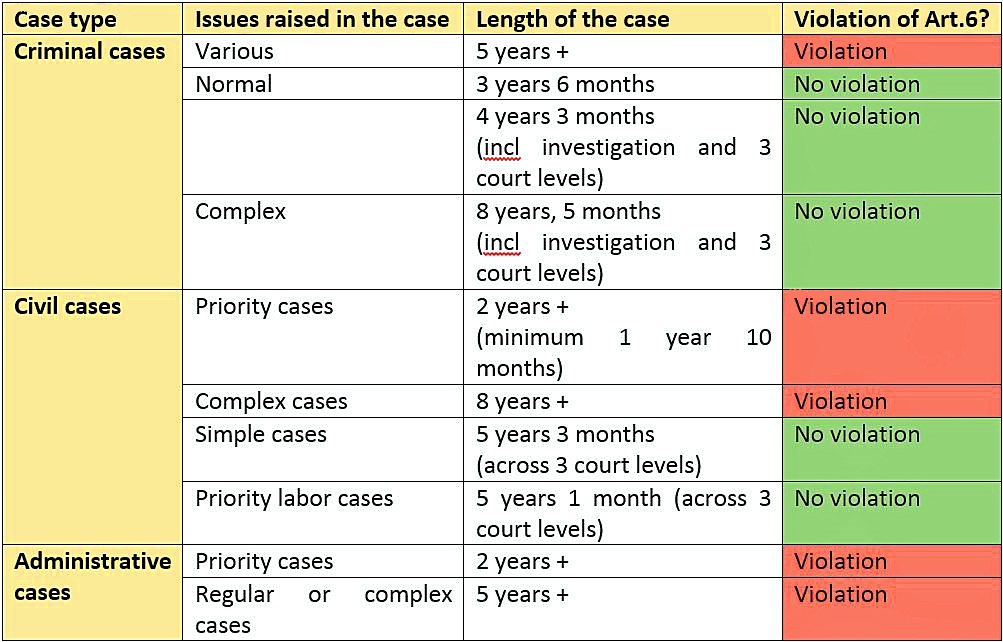

In an attempt to respond beyond rhetoric, I dusted off this old report by European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ). It may be ‘old news,’ but perhaps it’s an ‘oldie but a goody,’ with the findings reaffirmed in more recent reports here and here. The report analyzed a large number of decisions that had come before the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) and provided insights into what that the Court considers an ‘unreasonable time’ to be. (The ECHR interprets Article 6 of its Convention, which requires all 47 Council of Europe States to ensure within their jurisdictions that ‘everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time’.)

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) contains a similar provision which applies to all 168 of its states parties. This overlap means that the views of the ECHR provides a pertinent yardstick in ECA and beyond.

Despite what many people assume, there is no single international rule on how long cases should take. Each case must be considered on its own merits, but the following general ‘rules of thumb’ may be helpful.

Some courts have developed their own working definitions of ‘old’ or ‘delayed’ cases. In Kenya, any case is considered ‘backlogged’ if it’s older than 1 year. In Serbia, it’s 2 years. In Croatia, it’s 3.

But these general definitions aggregate all cases. In doing so, they can become more of a hindrance than a help. After all, an average person might reasonably expect their simple traffic case to be resolved in a shorter time – say 6 months. And two corporate titans in complex civil litigation might reasonably expect their duel to last more than 2 years.

The report provides a summary table of cases decided by the ECHR by case type. Of course, these are not timelines countries should aim at – countries can and should do better. But they provide some insight for when ‘justice delayed’ may be ‘justice denied’ and becomes a breach.

For some recent and applied examples of the Bank’s support to client countries in their efforts to understand and reduce court delays, check out the Serbia Judicial Functional Review and the Kenya National Case Audit and Institutional Capacity Survey.